As household wealth hits $176 trillion, a hidden workforce transformation is reshaping economic data

America added over 1,000 new millionaires every day in 2024, bringing the total to nearly 24 million, about 7% of the entire adult population. With household wealth reaching a record $176.3 trillion in Q2 2025, up $46 trillion since the pandemic began, the United States has never been wealthier on paper.

But this unprecedented wealth accumulation may be creating an economic blind spot that’s distorting how we interpret everything from to market performance.

As wealth concentrations reach levels not seen since the Gilded Age, a growing number of Americans are quietly exiting the workforce altogether: not because they’ve lost jobs, but because they no longer need them. This “wealth exodus” could be the missing piece in understanding why labor markets feel tight, asset prices keep climbing, and traditional economic indicators seem increasingly disconnected from ground-level reality.

The New Math of Financial Independence

The numbers tell a striking story. Labor force participation has mysteriously declined from 67.3% in 2000 to 62.4% in early 2025, even as unemployment remains near historic lows. Economists typically blame population aging, but prime-age participation (25-54) has actually recovered to near-record highs at 83.5%.

The real decline is concentrated among higher-income earners aged 55-65 who can afford early retirement, and increasingly, younger professionals pursuing “FIRE” (Financial Independence, Retire Early) strategies. The FIRE movement, once a fringe concept, has exploded into mainstream financial planning, with adherents saving 50-70% of their income to retire in their 30s and 40s.

Research from the ADP Institute confirms the wealth effect on work: as US household net worth climbed 190% over 20 years, Americans increasingly opted out of traditional employment. “As household wealth increases, people tend to work less or not at all,” noted researchers. It’s a trend that accelerated dramatically after 2020’s asset appreciation boom.

JPMorgan’s David Kelly warns that demographic trends combined with wealth accumulation could mean “no growth in workers at all” over the next five years. Labor force participation among prime-age workers has already declined from 62.65% to 62.22% in just one year (a loss of 1.2 million potential workers).

The Asset Storage Problem

Here’s where the story gets interesting for investors: $176 trillion in American wealth has to go somewhere. With traditional savings yielding minimal returns, wealthy Americans face what economists call the “asset storage problem”, which is, where to park massive wealth accumulations that continue growing faster than they can be consumed.

Stock ownership data reveals the bottleneck. While 62% of Americans own stocks, ownership is heavily concentrated by income. The top 20% of households drive most equity demand, with 87% of high earners owning stocks versus just 28% of lower-income households. Real estate and equities captured $6.7 trillion in wealth gains in Q2 2025 alone.

This creates a powerful feedback loop: asset appreciation generates more wealth, which creates more demand for assets, driving further appreciation. Meanwhile, those without significant assets experience an entirely different economy: one where wages struggle to keep pace with asset-driven inflation in housing, healthcare, and education.

A Second Gilded Age

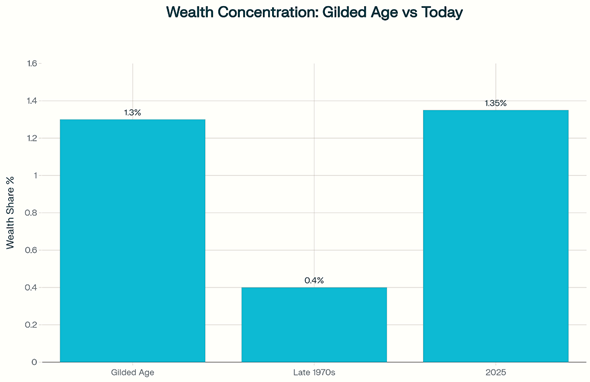

The wealth concentration levels support concerns about structural economic changes. Current data shows the wealthiest 0.00001% now control 1.35% of total U.S. wealth, exceeding Gilded Age levels for the first time since 1913. The top 0.01% (roughly 18,000 families) control 10% of national wealth, compared to just 2% in the late 1970s.

But there’s a crucial difference from the original Gilded Age. Turn-of-the-century robber barons built industrial monopolies that still required massive workforces. Today’s wealth concentration comes from financial asset appreciation during an era of unprecedented monetary expansion. Modern asset-wealthy Americans can exit the labor force entirely while their portfolios grow autonomously.

Cities like Scottsdale saw 125% millionaire population growth from 2014 to 2024, while West Palm Beach grew 112%. These aren’t random patterns, but they represent wealth migration hubs where high earners concentrate, often to enjoy early retirement in favorable tax jurisdictions.

Gilded Age vs Today – Wealth share held by the top 0.00001% of Americans: 1.3% in 1913, just 0.4% in the late 1970s, and 1.35% in 2025.

The Retirement Paradox

Perhaps most telling is the growing bifurcation in retirement preparedness. FIRE movement adherents and high earners are over-saving for early retirement, often accumulating 25-50 times their annual expenses. Some achieve financial independence by age 35, then spend decades managing investment portfolios rather than traditional careers.

Simultaneously, hardship withdrawals from 401(k)s hit record levels in 2025, with 4.8% of participants tapping retirement funds early, up from 1.7% in 2020. Some 37% of American workers have already raided their retirement accounts for immediate needs.

This creates a statistical anomaly: aggregate household wealth reaches records while individual financial stress also peaks. The averages mask the extremes, making traditional economic indicators increasingly unreliable guides to actual conditions.

Market Implications

If wealth-enabled workforce reduction is accelerating, it fundamentally reframes market interpretation. Low unemployment may reflect labor scarcity rather than economic strength. High asset prices may reflect structural demand from wealth storage needs rather than economic optimism. Consumer spending bifurcation may be permanent rather than cyclical.

The implications are profound:

Labor markets may face permanent constraints. As more Americans achieve financial independence, especially in high-skill sectors, wage pressures could persist regardless of economic cycles. Not a temporary pandemic disruption, but instead, a structural workforce reduction.

Asset demand may remain elevated. When a growing wealthy class needs to store wealth somewhere, and traditional savings offer minimal returns, equity and real estate markets become the default repositories. This creates upward price pressure independent of underlying economic fundamentals.

Economic data becomes misleading. Employment statistics, consumer spending patterns, and productivity measures all look different when a significant portion of the wealthy population operates outside traditional economic relationships.

Questions for Investors

As this wealth exodus potentially accelerates, several questions emerge:

How do you value companies in permanently tight labor markets? If wealth accumulation continues to reduce labor supply, businesses may face ongoing staffing constraints and wage inflation that traditional models don’t capture.

What happens to consumer discretionary spending? When high earners exit the workforce but continue consuming through investment income, does this create more stable demand for luxury goods and services?

Are current asset valuations justified by structural demand? If wealthy Americans have limited alternatives for wealth storage, could “expensive” markets actually represent fair value in a world of excess liquidity seeking homes?

How should monetary policy respond? Traditional tools assume employment and inflation trade-offs that may not apply when labor scarcity reflects wealth concentration rather than economic overheating.

The Path Forward

The data suggests we’re witnessing something historically unprecedented: voluntary mass workforce reduction driven by asset wealth accumulation during an era of extraordinary monetary expansion. Whether this proves sustainable (or leads to broader economic distortions), it may define the next phase of American capitalism.

For investors, understanding this hidden transformation could be crucial for portfolio positioning. Markets record all-time highs while traditional workers struggle isn’t just inequality. It may be structural economic evolution toward a system where asset ownership, not employment, increasingly determines economic participation.

The 560,000 Americans projected to become millionaires in 2025 aren’t just getting richer. They may be opting out of the traditional economy altogether, and taking their labor, spending patterns, and economic data with them. How markets and policymakers adapt to this new reality could determine whether America’s wealth boom becomes sustainable prosperity or an unstable bubble built on labor scarcity and asset concentration.

The wealth exodus has begun. The question is whether the rest of the economy can function without them.