Harvard’s Joint Center for Housing Studies of Harvard University recently released its 2025 update to “The State of the Nation’s Housing”. It’s always a thorough and data-rich report.

Although I think the report has a lot of valuable data and a good general review of the housing situation, I have to start with a complaint.

Homeowners Priced Out

The report shows rising home prices, mortgage rates, and monthly mortgage payments. The report says:

Home price appreciation combined with elevated interest rates to drive up homebuyers’ mortgage payments, pricing less affluent households out of the for-sale market… As of 2023, only 6 million of the nation’s nearly 46 million renters can meet this benchmark, according to the American Community Survey (ACS)… It is perhaps, then, not surprising that first-time homebuyers were older and more affluent in 2024.

Nevertheless, they increasingly relied on friends and family for help covering the downpayment, according to NAR’s 2025 survey of homebuyers and sellers. In this environment, annual growth in the number of homeowner households dropped from 1.25 million in 2023 to just 613,000 last year.

I have roughly replicated the Figure from the report here, and I have added the homeownership rate.

This is a common problem. Nothing they printed was false. But, it’s a good example of how microeconomic observations can’t be translated directly into macroeconomic conclusions.

One example of this problem would be to say that families are being priced out of Los Angeles. It is factually true in the micro sense. But it is meaningless in the macro sense. Los Angeles limits housing construction so that, say, 100,000 residents will need to move away in a given year. The way they decide who will have to move away is that everyone offers to rent available homes until 100,000 residents decide that the rent is too high.

The 100,000 movers is predetermined. The price depends on how much they fear displacement and, thus, how high the bids will rise before 100,000 cry uncle. Rising prices aren’t the cause of the displacement. They are the mechanism.

If we try to address displacement from Los Angeles by fixing prices (rent control, etc.), then some other mechanism will have to replace prices as the motivation for sorting families into displacement. Making prices lower cannot lower displacement from Los Angeles. So, “Families are being priced out of Los Angeles.” is simultaneously factually true and actively unhelpful as an observation about how to stop displacement from Los Angeles.

You could say the same about these comments from the JCHS. Surely if homes are more expensive, it is harder for families to afford them. This is what gets everyone to focus on affordability and mortgage rates against all evidence. All those comments from the JCHS are true, and they are actively unhelpful as observations about what is creating a crisis.

They note that homeowner household formation slowed down between 2023 and 2025. Well, guess what. Homeowner housing costs had stopped rising by 2023. You can see clearly in my Figure 1 that homeowner household formation is very strongly positively correlated with high homeowner costs.

Cyclically, homeowner demand is driving owner costs up (and likely is associated in complicated ways with rising mortgage rates).

Clearly, during this period, there is a secular supply problem that is creating an upward slope on housing costs of, say, 40% per decade. There are cyclical swings from changing demand for homeownership that should be swinging housing construction up and down over the cycle, but since we block housing construction, it creates cyclical price appreciation instead.

And, third, we imposed a massive one-time shock to mortgage access (which is a very different issue than changing rates) which created a one-time downward shock of 40 points in home prices (and likely was associated in complicated ways with declining mortgage rates) and a one-time downward shock of 5 percentage points in homeownership. (That measure should have an upward trend because of age demographics.

Increasingly, ownership is free and clear. The increase in homeownership before 2008 was related to greater use of mortgages, but the recent increase has been balanced growth between mortgaged and unmortgaged ownership.)

To say that high costs are “pricing less affluent households out of the for-sale market” is factually true and actively unhelpful as an observation about what is wrong with housing.

The “priced out” framing can make it seem like mortgage access or new capital in the market for rental homes are problems, because their first-order effect would be to create more buyer demand, which would put upward pressure on prices.

More buyers (which are suppliers) is good. I’m afraid the “priced out” framing does more potential damage than good.

An analogy you might have read here before is that the price of homes is like the price of farmland, and rent is like the price of bread.

There are many ways to cause the price of farmland to inflate. Some are good and some are bad.

If the price of bread is high, then it is natural for the price of farmland to rise to reflect the need to make more bread. If the price of bread is high, it isn’t helpful to fret that the rising price of farmland is pricing less affluent farmers out of the market. We need more bread, so we’re going to need more farmers. (And the high price of bread naturally induces new farmers to buy more farmland.)

The prevalence of the equivalent of “subsistence farmers” (homeowners) in the market for housing can create confusion on this issue, but it doesn’t change the underlying truth.

Prices are high because rents are high.

Renters Priced Out

The following sections show the real problem. Rents are rising, which is the reason home prices are rising. They show that, even with the recent rise in completed apartments, the number of rental tenants has increased to match it. That will generally continue to be the case. There are millions of households waiting to form, if there was a house for them to form in, and most of them have been consigned to rental status.

In Figure 4, they show that cost burdens are rising. In 2021, 16 million homeowners were cost burdened. In 2023 it was 20 million. Over the same period, cost burdened renters rose from 15 million to 23 million.

Unfortunately, I have another complaint here. The report notes, “While new construction has grown the rental supply overall, it has failed to increase the stock of low-rent units, which has dwindled over time. Between 2013 and 2023, the number of units renting for less than $1,000 per month after adjusting for inflation fell by more than 30 percent, from 24.8 million to 17.2 million. Instead, new construction focused primarily on higher-rent units, which helped to nearly triple the stock that rents for $2,000 or more, from 3.6 million to 9.1 million during the same period.”

No. Just no. Housing doesn’t get more expensive because developers build more expensing housing. I would have expected a more sophisticated understanding.

They claim that the number of apartments renting for $2,000 or more increased by 5.5 million units over a decade. There were less than 3.5 million apartment units, total, completed over that decade. The problem isn’t that we built too many “high rent” units. Come, on.

Later, the report notes trends coming after the recent increase in apartment completions. “Asking rents rose 1.8 percent in Class A apartments and 0.9 percent in Class B apartments year over year. Rents in lower-quality Class C apartments dropped by 0.7 percent.” Did builders start building cheaper apartments?

In the defense of the report’s authors, later in the report, they do note that, “The wave of apartment construction should have longer-term benefits as higher-income households move into newer apartments, freeing the existing stock for those with lower incomes.” The authors of that section of the report should have a talk with the authors of this section of the report.

Household Growth

The report notes that household formation had bottomed around 600,000 annually after 2008, then rose up to around 1.6 million annually for the most recent few years. In the first quarter of 2025, it has dropped to a pace of about 1.2 million households. They forecast that for the next decade, household formation will decline further, totaling around 7 to 8 million for the decade.

That’s probably a reasonable estimation of neutral household formation. And, most of that is from immigration, so the Trump administration could push that lower.

The report notes that, “The outsized level of household growth among younger adults was largely due to an inherently temporary return of ‘missing’ households whose formation was delayed by the Great Recession… In 2024, however, the rebound in young adult headship rates ended, with formations among younger adults entirely driven by underlying population growth.”

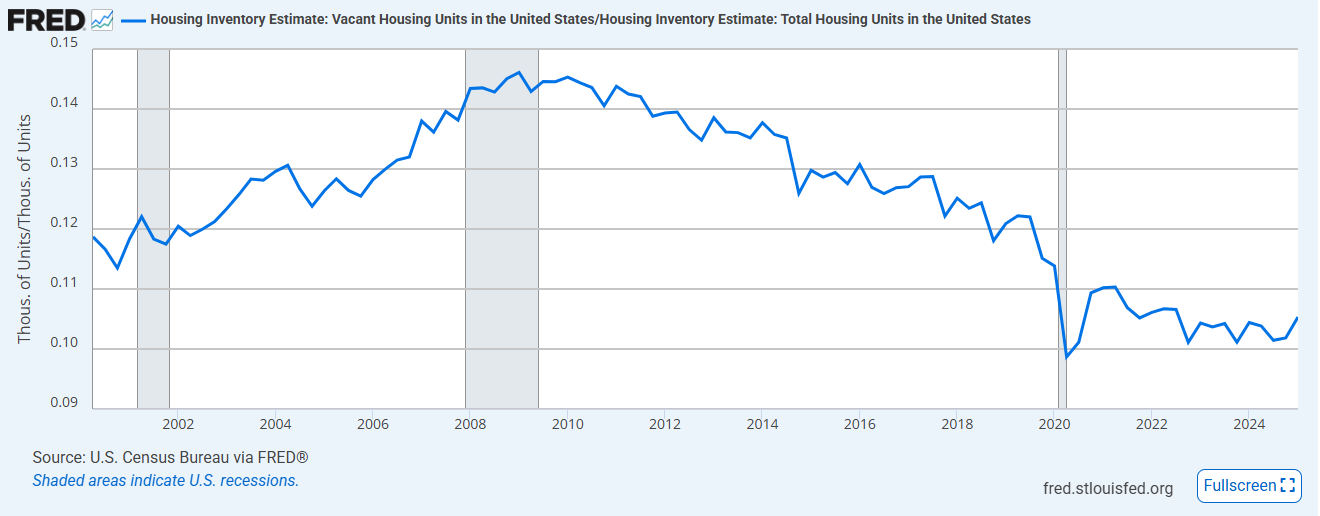

This is very useful data. However, I have a very different expectation. Household formation since the Great Recession has outpaced new home completions. The rebound in households was harvesting vacant homes from the existing stock of homes. I think that by 2024, we had tapped that vein of supply about as strongly as we can. Vacancies can’t functionally get any lower than this.

In 2025, household formation is dependent on new home completions. Completions are currently running at a pace of about 1.5 to 1.6 million units annually, and that number is limited by current input capacity. Factoring in some losses from the existing stock of homes, there was little room for household formation above 1.2 million this year.

I think it is far too premature to call the end of the household formation rebound. There are more than 10 million additional households that would form if the supply was there. And, in the process of providing that supply, we would also end up creating another 5 million vacant units, which would lift markets back to a more typical balance.

There easily is demand for more than 20 million new units in the next decade. And, frankly, the cost burden data doesn’t make any sense if that’s not the case.

They forecast only about 4 million net new households from 2035 to 2045. If we build 20 million units this decade, there would likely be room for a decline in construction by then. After the shortage is filled, increasingly, residential investment will transition to a market that is driven more by replacement than by growth needs, but that is tens of millions of units and trillions of dollars of improvements in the future.

Renter Incomes

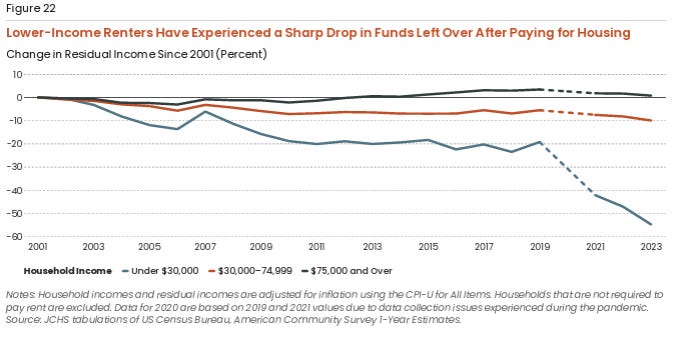

It’s sad to see my own analysis confirmed in the report. Renters with lower income are losing ground. They are poorer each year.

They show even middle-income renters losing ground. That makes sense. My analysis used rental value on all homes, but homeowners are hedged against rising rents. Within a given ZIP code where residual income after housing expenses is moderately positive, it makes sense that it is actually more positive among homeowners and more negative among renters. My analysis might have been optimistic in that sense.

Single-Family Rentals

The report notes the recent spike in new single-family homes built-to-rent. It notes that this form of rental can meet the needs of local markets that are short of rental options. Unfortunately, the section ends with:

As investor activity in the single-family rental market increases, observers have voiced concerns that would-be homebuyers are losing the chance to purchase these properties. According to Cotality, investors bought nearly a third of single-family homes sold in the first quarter of 2025 (31 percent), much higher than the 19 percent purchased in the same quarter of 2019. Individuals struggle to compete with large investors that can buy homes with cash or more easily secure financing, close deals quickly, and purchase several properties in a single transaction. Such investors target modestly priced homes and have been especially active in growing Sun Belt markets. In response, lawmakers across several states have proposed legislation to prioritize sales to individuals.

It’s unfortunate that the authors didn’t feel motivated to rebut those concerns rather than simply state them. Those concerns are like a dormant pathogen in our economy and need to be fumigated.

Conclusion

The report also includes helpful data on rising homelessness and a discussion of recent trends in local land use reforms. Notwithstanding my quibbles above, it is a handy annual review of American housing conditions.