Thursday marked the 24th anniversary of the September 11 terror attack on the World Trade Center and Pentagon – the very definition of a “black swan” event – a term developed by author Nassim Taleb for “a highly improbable, unpredictable event with massive consequences.” The literal meaning of the term is that white swans are so common that a “black-swan,” on first sight, doesn’t seem like a swan at all – or any other known species. (Actually, in nature, black swans are quite common in Australia, but very rare in the Northern Hemisphere, where most black-swans have escaped from zoos or private ownership).

By definition, “black swan” events are impossible to predict, but they define our memories, in traumas like Pearl Harbor (1941), the JFK assassination (1963), the 1987 market crash, 9/11/2001, or COVID.

Most of these unexpected shocks don’t cause any long-term market disruption. For instance, Hitler’s surprise attack on Poland on September 1, 1939, didn’t hurt the market at all. It rose for the next 12 days. Also, the stock market rose strongly the week after the murder of President Kennedy in 1963, and the market quickly recovered from the September 11, 2001 attack on America. But before getting into these market reactions, I’d like to note some other black swans that flew over America on September 11:

1609: We can only imagine how Native Americans viewed the apparition of a white-sailed “air-water-wind canoe” on September 11, 1609. Edward Moran’s painting (below) reflects their Black Swan-like apprehension of an attack on America in New York harbor, when Henry Hudson entered a river soon to be named after him, landing in Manhattan and shocking the natives, before sailing up the Hudson River.

1683: Maybe Osama bin Laden studied history, too, since Islamic armies had been stymied on the other side of the world, twice, on 9/11. First, the Ottoman Empire advanced through the Balkans and deep into Europe before finally meeting its Waterloo in Vienna on September 11, 1683, in a remarkable (some say miraculous) counterattack by united forces under Poland’s King John Sobieski in the battle of Vienna.

1818: Also, the Saudi state under the Wahhabi sect was defeated by the invading Egyptians on September 11.

1776: The British invaded Manhattan again on 9/11. After taking Long Island and Brooklyn in August, British General Howe met in a “ceasefire” negotiation with John Adams and Ben Franklin on Staten Island on September 11, 1776, giving General George Washington time to move his troops up to Harlem.

1777: In the Battle of Brandywine, Pennsylvania, on September 11, 1777, British and Hessian troops under General William Howe defeated American forces under General George Washington.

1814: America fought back in a second war with Britain on September 11, 1814, at the Battle of Lake Champlain in New York, employing a new U.S. fleet under Master Commandant Thomas MacFonough.

1857: Another market-oriented Black Swan flew (or sank) Wall Street’s hopes on September 11, 1857, when the ship U.S. Central America, carrying a large shipment of gold and nouveau riche passengers, was caught in a hurricane off the coast of South Carolina. After a heroic struggle against wind, waves, and water, the ship sank the next day at the cost of 423 lives and a cargo of 80,000-Troy ounces in gold coins from the San Francisco mint. That loss, small by today’s standards, greatly deepened the Panic of 1857.

1899: Another kind of Black Swin hit Yakutat Bay, Alaska, on September 11, 1899, with an earthquake causing the largest vertical displacement ever recorded: Shorelines rose over 47 feet in one area, but very few people lived in that part of Alaska, so there were no known casualties, unlike what struck next year:

1900: On September 9, 1900, Galveston, Texas, was struck by the deadliest natural disaster in American history, killing at least 8,000, with maximum sustained winds of 145 mph lasting 18 hours. Galveston was rebuilt, eventually, but further inland and about 15 feet higher. (See “Isaac’s Storm” by Erik Larsen).

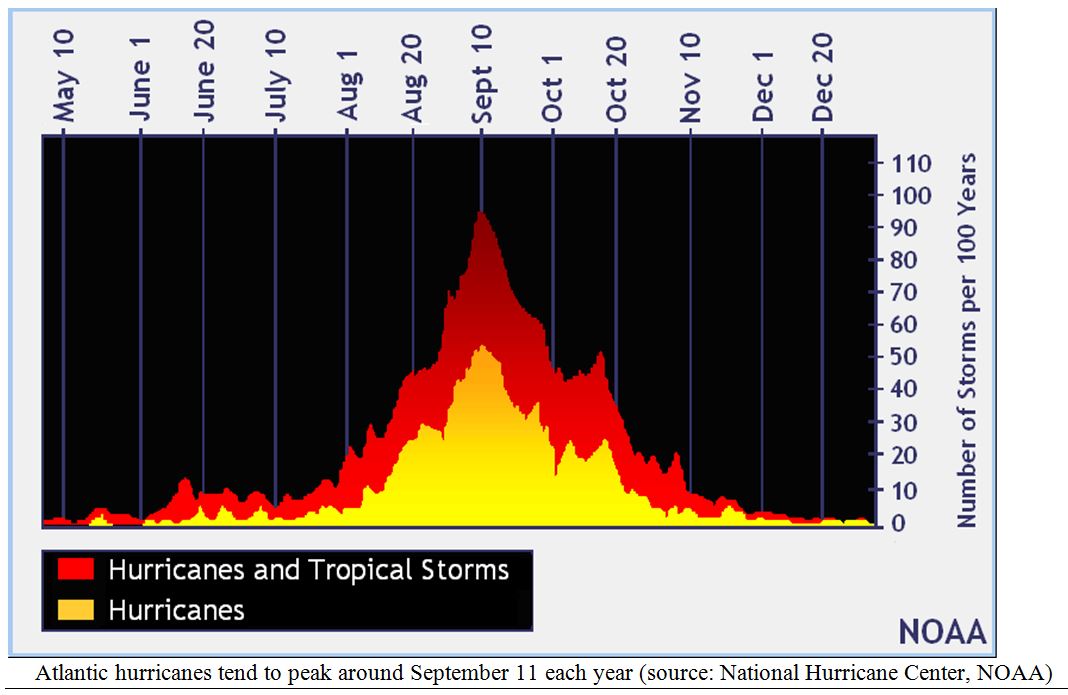

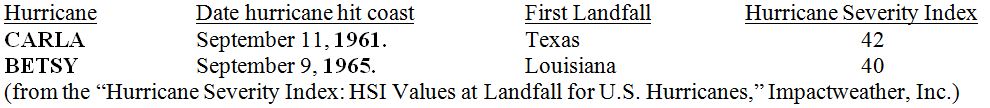

Using the Hurricane Severity Index, which measures hurricanes by intensity and size on a scale of 1 to 25, then adding the two numbers together, the two most intense hurricanes in U.S. history hit the Gulf (of America?) on September 9 and 11 in the 1960s, mirroring the peak hurricane date of September 10 (above).

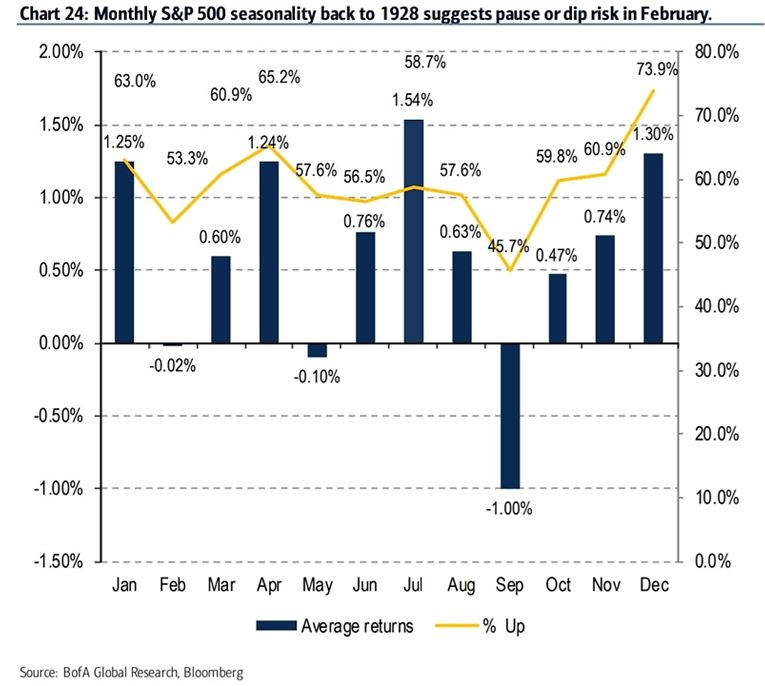

September is also the peak of “hurricane season” on Wall Street as well as the Gulf Coast. Historically, September is the worst month in market history – for nearly a century (since 1928), and by a long shot:

October has delivered several scares, but most October crashes began with long, deep September drops.

More Wall Street News on or Near September 11

1789: Three years before “Wall Street” was born, on September 11, 1789, Alexander Hamilton became our first Secretary of the Treasury, fittingly to serve on Wall Street as our nation’s first cabinet officer.

1901: On September 9, 1901, New York Stock Exchange (NYSE) officials laid the cornerstone for a new stock exchange building at 18 Broad Street. It was finished in 1903 and is still operational today.

1920: The second-worst Black Swan event in New York City hit Wall Street head-on. On September 16, a shrapnel-laden cart was parked in front of at Wall & Broad and then detonated shortly after noon, killing 38 and injuring hundreds, as they stepped out for lunch. At the time, America’s “Red Scare” dominated the news. Anarchists were seemingly on the loose, and such bomb scares were common.

Theories abounded, but the perpetrator fled the country, and the conspirators were never caught. But the next day was business as usual, with many workers in bandages removing debris and cleaning the area.

Before September 11, 2001, market hurricanes often struck this week in the volatile 1970s and 1980s:

- On September 8, 1974 (a Sunday), President Gerald Ford pardoned former President Richard Nixon for any crimes that he may have committed while in office. On the next Monday morning, the market continued its long 20-month free-fall: In the week of September 9-13, the S&P 500 fell by 8.7%.

- On Friday, September 8, 1978, the Dow had a great day, rising to an interim peak of 907.74, but that marked the high point of the late 1970s. The Dow then fell by 16.4% into early 1980. In the week of September 11-15, 1978, the Dow fell 3.2%, and then it fell a total of 11.3% by year’s end.

- On September 11, 1986, the Dow fell 86.61 points to 1792.89, the largest daily point loss – and the highest volume (237.57 million) – in market history, to that date. There was NO real news, but on the next day, Friday, September 12, a record 240.5 million shares traded on the Big Board, breaking the previous day’s record. For the week ending September 12, 1986, the Dow fell 8.4%, from 1919 to 1758. However, the Dow would gain 55% within 12 months, mostly on a huge new tax cut bill!

- On September 9, 1987, the new Fed Chair, Alan Greenspan, made a preemptive strike against phantom inflation by raising the Discount Rate half a percent (50-basis points), and the Dow fell 62 points (-2.5%). This rookie blunder turned out to be the first warning shot of the Crash of 1987.

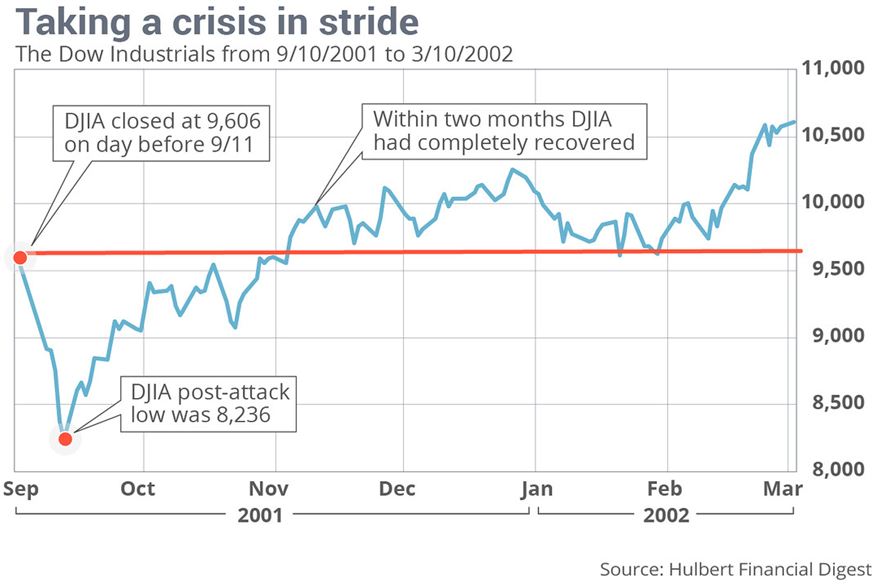

- On Monday, September 10, 2001, by contrast, the Dow changed by less than half a point, falling from 9605.9 to 9605.5. Then all hell broke loose on Tuesday, but the key point to remember is that the market recovered fully by Thanksgiving. As usual, Americans become more resilient when facing threats.

On September 11, 2008, the stock market posted small gains. Still, Wall Street was teetering on the edge of a major financial crisis that would explode the following week, following the bankruptcy of Lehman Brothers on Monday, September 15. The market continued down, but for just six months.

It took longer for the stock market to recover after the 2008 crash than after most other black swan events, but we went on to set a record for the longest bull market, from 2009 to 2020, ending only due to COVID.

The lesson from these and other historical crises: This will pass. Don’t panic when everyone else does.

Black Swans will eventually fly away, only to strike again some other day in another unpredictable event.